Posted by Roslyn Green in September 2022

der Hauself – the house elf

Dobby is not just a free elf. He is also a noun.

die Nase – the nose

Dobby hat eine lange, spitze Nase. – Dobby has a long, pointy nose.

The parts of his elvish body are common nouns and must be capitalised in German.

das Auge – the eye

Dobby hat auch große Augen. – Dobby also has large eyes.

Common nouns are always capitalised in German, along with all other nouns.

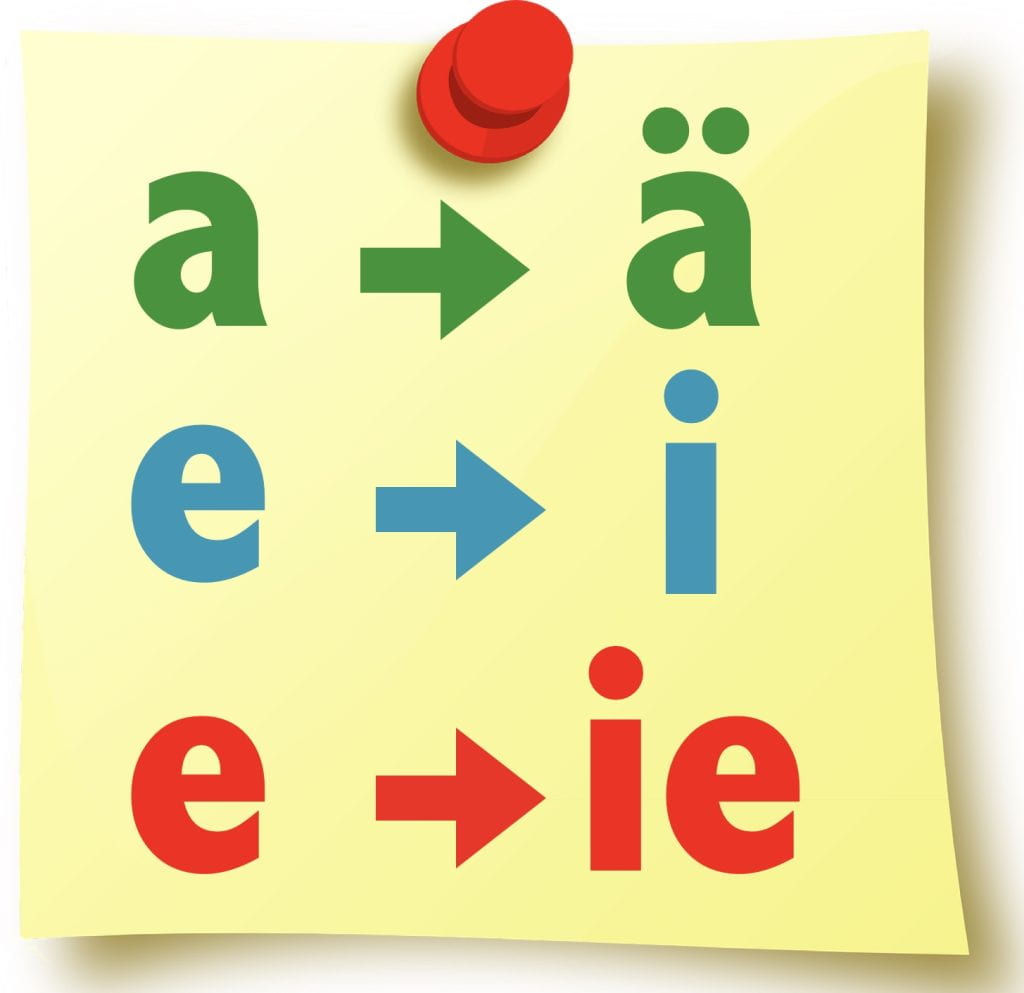

So this is how German capitalisation rules look in an English text:

The young Girl sat in the Courtyard reading a Book. She had a sweet, kindly Face, with dark brown Eyes and long black Hair. To the shy Boy, she seemed almost to glow in the Sunshine.

Although she was in his Class, he scarcely dared to approach her. For one Thing, she was deeply absorbed in her Homework, looking up Words in her Dictionary.

Then suddenly she saw him and gave him a Smile. She was wearing Braces.

“At least her Teeth aren’t perfect,” he thought with Relief. “And she has lots of Freckles on her Nose.“

It was actually those friendly Freckles that finally gave the Boy the Courage to speak.

OK, it’s a sappy English love story in the making, but the noun capitalisation is pure German.

Words Requiring a Capital in German

- The names of countries: Deutschland, Neuseeland, Australien, China

- The names of languages: Deutsch, Englisch, Chinesisch

- The names of cities: Berlin, München, Melbourne

- People’s names (but not the first person subject pronoun, ich)

- Common nouns relating to everyday concepts and objects: das Handy (mobile phone), der Geburtstag (birthday), die Idee (idea), etc.

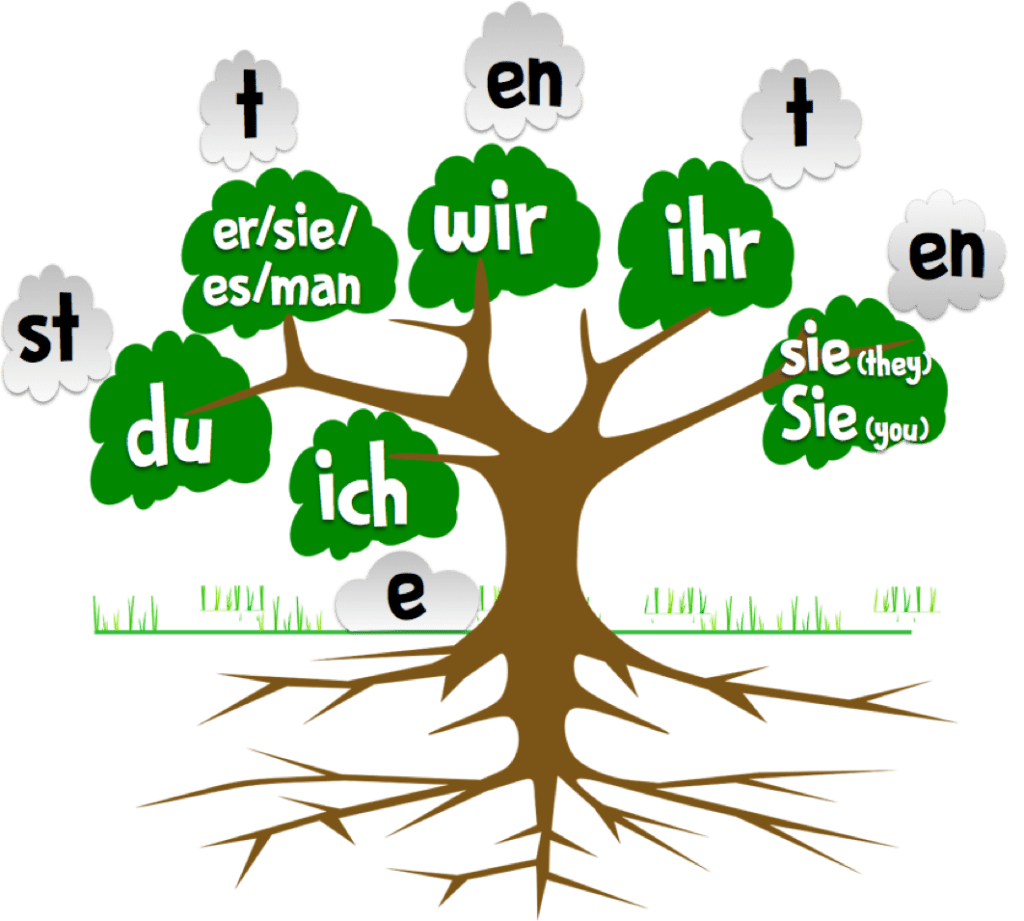

A word is always a noun if:

- it can have der, die or das placed before it – or any other form of the definite article.

- it can have ein, eine or einen placed before it – or any other form of the indefinite article.

- it can be possessed, as indicated by a possessive term like mein, dein, etc.

- it can be counted – e.g. 20 books, 20 Bücher

- it can be described with an adjective – e.g. a free elf, ein freier Elf

A Quiz to Practise German Capitalisation

Quiz: Capitalising Nouns in German – With Dobby’s Help ![]()

A short story of Dobby’s life: find the missing capitals (quiz embedded below)